In

1976, Jesse Hardy bought 160 acres of swampland that nobody else wanted. And he

intends to keep it.

EAST OF NAPLES, TURN LEFT

AT THE BUCKET - Once, the land under Jesse Hardy's feet was an underwater reef,

and nobody owned it and nobody wanted it.

Then it became more or

less solid, part of South Florida . To the

east, the Everglades grew drier and drier. To

the west, a town called Naples Miami

It was harsh, unlovely

land, miles from anything, with rocky ground, slash pines, swamp cabbage and

sand gnat swarms so thick he had to hold his breath. No electricity or sewer or

water. Hardy built a shed, then a house. Dug a well. For 30 years, nobody

bothered him. Now they won't leave him alone.

The state wants to buy

Hardy's property for its $8-billion Everglades

restoration project, which, in theory, would flood his land and everything

around it. But first, Hardy has to get out of the way, and he is not inclined

to go.

"They're trying to

get rid of me right here," says Hardy, 69. "This here land was not

worth nothing. I sat here and loved it. It ain't much, but it's been good to

me."

Hardy paid $60,000 for

his 160 acres, now valued for tax purposes at $860,000. The state offered him

$711,725 in 2002. He said no.

It offered him

$1.2-million in 2003. He said no.

$1.5-million? No.

$4.5-million? No. No. No.

"I know I'm fighting

a hell of a big person. I'm fighting the governor of Florida

"What they're trying

to do is take all the humans . . . bunch up people like in real close

proximity, get all the people in one damn bunch so they can say, "Don't go

out over there! A chicken'll get ya!'

"They're trying to

stop a way of life."

* * *

Some people say the

Everglades Restoration Plan is the nation's largest, most important ecological

project. Jesse Hardy is not one of those people.

The idea is to tear up

the roads and plug the canals so freshwater flows from Lake

Okeechobee to the ocean like juice spilled on a countertop, giving

habitat back to the panthers and wading birds.

Hardy insists he's not in

the Everglades , and the state can do its

science experiment without his contribution.

"The Everglades is 30 miles east, thataway," he says,

pointing.

His lawyer, Karen

Budd-Falen of Wyoming

"I think the state

just wants the land," she says. "He's out in the middle of nowhere,

and they don't want anybody out there."

The state would make his

land part of Picayune

Strand State

Forest

The state has already

bought or taken 1,859 parcels - more than 54,000 acres - between Interstate 75

and U.S. 41. Only the Miccosukee Indians and Hardy are still hanging on. Hardy

is the last remaining homesteader.

"There's nobody

left," Budd-Falen said.

* * *

Although Hardy is famous

and gracious with visitors, he's still sometimes portrayed as a hermit or a

swamp rat. Call him that and he will begin to cuss.

He built the house

himself, drilled the wells himself with a bit he made himself. Ask how he

learned to do these things and he will say, "I got me a book."

Life was pretty crude in

the beginning. He'd wait for a warm day to take a shower. But now he has air

conditioning, reverse osmosis, a washing machine, a cell phone, a satellite

dish. He has solar panels on the roof and a big generator out back.

He reads newspapers and

loyally watches Greta Van Susteren and Hardball. He's showing off his bathroom

- "I don't need no gold-plated plumbing to get me a good shower" -

when a Fox News alert informs him that we could all die any day.

"All they do is talk

about who's going to blow us up next," he says, and then he launches into

an analysis of the situation in the Middle East .

He lives here with a

family friend, Tara Hilton. They've never been romantically involved, but he

took her in when her son was born nine years ago. Hardy raises Tommy as his

son, plays Frisbee and basketball with him, pays for his $45-an-hour tutor,

hangs his crayon art on the walls.

"He never would've

had no chance for no daddy or nothing," Hardy says.

He supports his family

and pays his lawyers with a sizable limestone mining operation. A couple of

hundred trucks run on and off his land every day, hauling $18 profit each.

The pits fill with water

from below the surface, and he stocks them with catfish, bream and turtles. He

wants to run a fish farm here and leave it to Tommy when he's gone. So far,

Tommy won't eat the fish they catch here. He thinks they're pets.

With the money the state

has offered, Hardy could live pretty much wherever he wants. But he's already

there. Girlfriends have told him it's too lonely here. But he has never felt

that way.

"Let me tell you

about being lonely," he says. "You could be in a roomful of people

and be lonely as hell. I've been in Miami

* * *

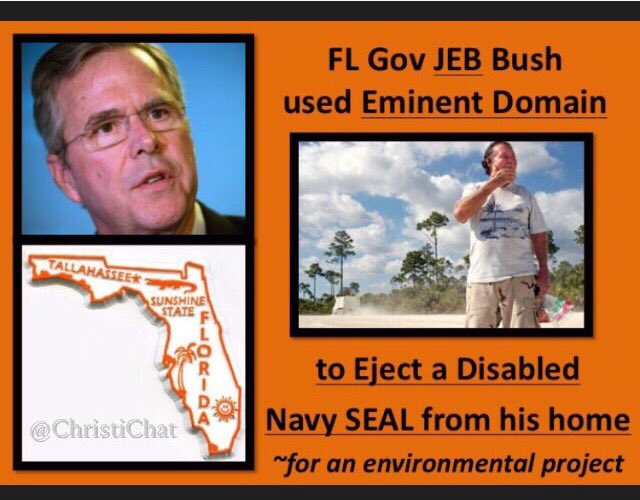

In April, when Hardy was

in the hospital with prostate cancer, Tara and Tommy went to Tallahassee

"We want to do it so

the people of Collier

County

She told him how deer

come up to the house windows. And about the wild boar - "a piney wood

rooter" - that came out of the woods and started living under the house.

That made the governor chuckle.

"We're not trying to

stop any projects," she said. "If you would just let us stay and it

floods, we'll swim out and give you the land."

Gov. Jeb Bush asked his

staff to look at ways to work around Hardy, or let him sign away his right to

sue if he ended up treading water.

"I'm just breaking

out in a rash just thinking about this," Bush said. He shook Tommy's hand.

But his staff said

letting Hardy stay won't work. In May, Bush ordered eminent domain proceedings

so the state can force Hardy off.

All the players will sit

down for formal mediation in March - more offers and counteroffers. If that

doesn't work, they'll have a two-day hearing, probably in April. Hardy's

attorneys have also filed suit in federal court. They can't predict how this

will turn out.

"Who knows?"

Budd-Falen said. "But I think a lot of people underestimate Jesse Hardy,

that's for sure."

* * *

There has been a lot of

talk lately about what the land is worth.

"That's a hard

question," Hardy says. "It depends what they're going to let you do

with it. I could put houses, an RV park, make a fortune. Hell, I could have

trailers lined up here to Timbuktu

But that's not really

what he wants. And he says it's not the point.

"This is mine,"

he says. "This is mine, by God. It's my damn land. It ain't for

sale."

The first time he saw it,

it reminded him of land he would look at through fences as a little boy.

He grew up around Port

St. Joe, where the St. Joe Paper Co. owned almost a million acres. Its paper

mill opened when Hardy was 3, and he hated the mill and the company his whole

life.

He grew up without

electricity on an acre or two in the woods. His mother took in laundry, washed

it in a pot and hung it on a line. She tried to move them away from the mill,

but the stink followed.

"It was a brutal g-

d-- mill," he says. "Mama said it's killin' all of us. The fumes were

so bad she couldn't hang clothes. She'd say that stink is dripping out of the

sky."

The paper company cut

ditches and rights of way and put up fences. Now a realty company, it is still

the largest private landowner in the state. As a kid, Hardy couldn't find land

to hunt or fish. The oysters and clams in St. Joseph Bay

"I knew land was

power because I couldn't get to it," he says. "I learned that as a

kid because we couldn't go hunting, we couldn't go fishing or nothing. I've

never had anything."

He left the Panhandle for

the Navy SEALs, where he was disabled in a training jump. When he got out, he

got a real estate license and worked as a property appraiser in Miami

His 160 acres of swamp

was the first land he ever bought.

"This is all I've

ever owned," he says. "I knew it was power."

Hardy is pitching whole

slices of moldy bread into his fish pond. The big oscars are attacking like

terriers.

"I love

nature," he says. "I've got more environmentalist in my little finger

than they've got."

He's talking about the

state Department of Environmental Protection. And the Florida Wildlife

Federation and the Audubon Society and the South Florida Water Management

District and everyone else who has ganged up to pressure him to sell.

"The

environmentalists, that is our problem," Hardy says. "That's America

"I'm not talking

about no scorched-earth policy. What I'm talking about is sense. We're up to

our armpits in alligators because people are just crazy. They're fanatics.

"In the paper today,

there's a story about damn red-cockaded woodpeckers and they're saving them and

going through all kind of hell. People are not running around shooting

red-cockaded woodpeckers. I haven't shot one in 20 or 30 years.

"God, spare me from

the damn environmentalists, 'cause they are the cause of me being in the jam

I'm in."

* * *

Nancy Payton is one of

those damn environmentalists.

To her face, "it's

usually Ms. Payton," she says. She represents the Florida Wildlife

Federation, which supports the restoration plan. She has dealt with Hardy for

years.

She's heard about how

much he loves his land. She's skeptical about that.

"I have a hard time

digesting "I love the land, but I'll sell it off truckload by truckload,'

" she says. "I think it is about the money."

She says his limestone

operation is bad for the environment because his ponds interrupt the way the

land drains. Hardy and his attorney dispute that.

Payton acknowledges that

Hardy has a fan base in Naples

"He periodically

gets a lot of coverage because he is kind of likable," Payton said.

"There are also people who are a bit exasperated."

Budd-Falen, Hardy's

attorney, grew up on a fifth-generation cattle ranch. She said it can be hard

even for people who love the environment to understand people like Jesse Hardy.

"Sometimes

environmentalists are not about protecting the environment, they're about

stopping use," she says. "Isn't that what the King of Nottingham did

in Robin Hood?"

Hardy acknowledges that

he makes money off his land, although he sends a lot of it to lawyers.

He says he doesn't need

it. He doesn't really want anything except to leave something to Tommy.

"I don't need no

cruises," he says. "I went on some nice long cruises in the

Navy."

He says he fights because

it's in him to fight. But he also says this land is what he has to leave

behind.

"It's for the people

of Collier County

If the state gets the

land, he figures they'll put a fence around it.

He can't stand the

thought of that. Of some little boy on the other side of it, looking in.

-- Kelley Benham can be

reached at 727 893-8848 or benham@sptimes.com

If you'd like to know

more about the Everglades Restoration Plan, click on www.evergladesplan.org Jesse Hardy's Web site is www.jessehardy.com

[Last modified February

28, 2005, 17:04:02]

No comments:

Post a Comment

Got something to add? Easiest if you use the Anonymous as the profile. But hey.. what do I know. If you want to criticize or lambast me please feel free to do so. . . In advance, Thanks